KubeVirt Security Fundamentals

Security Guidelines

In KubeVirt, our approach to security can be summed up by adhering to the following guidelines.

-

Maintain the principle of least privilege for all our components, meaning each component only has access to exactly the minimum privileges required to operate.

-

Establish boundaries between trusted vs untrusted components. In our case, an untrusted component is typically anything that executes user third party logic.

-

Inter-component network communication must be secured by TLS with mutual peer authentication.

Let’s take a look at what each of these guidelines mean for us practically when it comes to KubeVirt’s design.

The Principle of Least Privilege

By limiting each component to only the exact privileges it needs to operate, we reduce the blast radius that occurs if a component is compromised.

Here’s a simple and rather obvious example. If a component needs access to a secret in a specific namespace, then we give that component read-only access to that single secret and not access to read all secrets. If that component is compromised, we’ve then limited the blast radius for what can be exploited.

For KubeVirt, the principle of least privilege can be broken into two categories.

Cluster Level Access: The resources and APIs a component is permitted to access on the cluster.

Host Level Access: The local resources a component is permitted to access on the host it is running on.

Cluster Level Access

For cluster level access the primary tools we have to grant and restrict access to cluster resources are cluster Namespaces and RBAC (Role Based Access Control). Each KubeVirt component only has access to the exact RBAC permissions within the limited set of Namespaces it requires to operate.

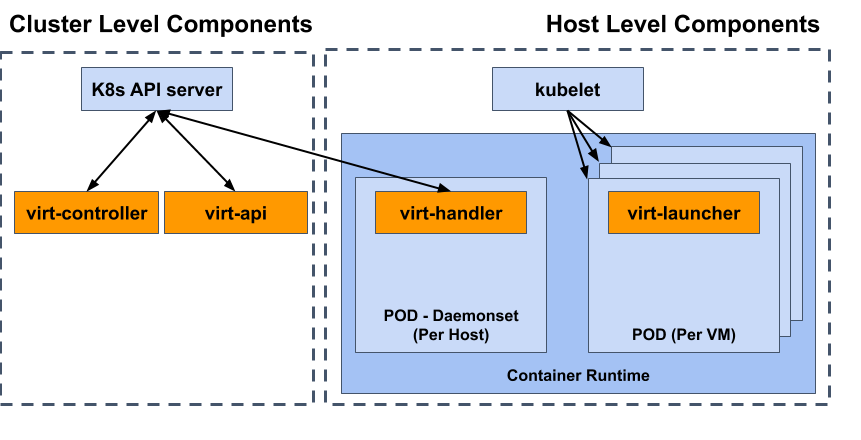

For example, let’s take a look at the KubeVirt control plane and runtime components highlighted in orange below.

Virt-controller is the component responsible for spinning up pods across the entire cluster for virtual machines to live in. As a result, this component needs access to RBAC permissions to manage pods. However, another part of virt-controller’s operation involves needing access to a single secret that contains its TLS certificate information. We aren’t going to give virt-controller access to manage secrets as well as pods simply because it needs access to read a single secret. In fact we aren’t even going to give virt-controller direct API access to any secrets at all. Instead we use the ability to pass a cluster secret as a pod volume into the virt-controller’s pod in order to provide read-only access.

Virt-api is the component that validates our api and provides virtual machine console and VNC access. This component doesn’t need access to create Pods like virt-controller does. Instead it mostly only requires read and modify access to existing KubeVirt API objects. As a result, if virt-api is compromised the blast radius is mostly limited to KubeVirt objects.

Virt-handler is a privileged daemonset that resides at the host level on every node that is capable of spinning up KubeVirt virtual machines. This component needs cluster access to the KubeVirt VirtualMachineInstance objects in order to manage the startup flow of virtual machines. However it doesn’t need cluster access to the pod objects the virtual machines live in. Similar to virt-api, what little cluster access this component has is mostly read-only and limited to the KubeVirt API.

Virt-launcher is a non-privileged component that resides in every virtual machine’s pod. This component is responsible for starting and monitoring the qemu-kvm process. Since this process lives within an “untrusted” environment that is executing third party logic, we’ve designed this component to require no cluster API access. As a result, this pod only receives the default service account for the namespace the pod resides in. If virt-launcher is compromised, cluster API access should not be impacted.

Host Level Access

For host level access, the primary tools we have at our disposal for limiting access primarily reside within the Pod specification’s securityContext section. It’s here that we can define settings like what local user a container runs with, whether a container has access to host namespaces, and SELinux related options. Other tools for host level access involve exposing hostPath volumes for shared host directory access and DevicePlugins to pass host devices into the pod environment.

Let’s take a look at a few examples of how host access is managed for our components.

Virt-controller and virt-api are cluster level components only, and have no need for access to host resources. These components run as non-privileged and non-root within their own isolated namespaces. No special host level access is granted to these components. For OpenShift clusters, the SCC (Security Context Constraint) feature even provides the ability to restrict virt-controller’s permissions in a way that prevents it from creating pods with host access.

Virt-launcher is a host level component that is non-privileged and untrusted. However this component still needs access to host level devices (like /dev/kvm, gpus, and network devices) in order to start the virtual machine. Through the use of the Kubernetes Device Plugin feature, we can expose host devices into a pod’s environment in a controlled way that doesn’t compromise namespace isolation or require hostPath volumes.

Virt-handler is a host level component that is both privileged and trusted. This component’s responsibilities involve reaching into the virt-launcher’s pod to perform actions we don’t want the untrusted virt-launcher component to have permissions to perform itself. The primary method we have to restrict virt-handler’s access to the host is through SELinux. Since virt-handler requires maintaining some limited persistent state, hostPath volumes are also utilized to allow virt-handler to store persistent information on the host that can persist through virt-handler updates.

Trusted vs Untrusted Components

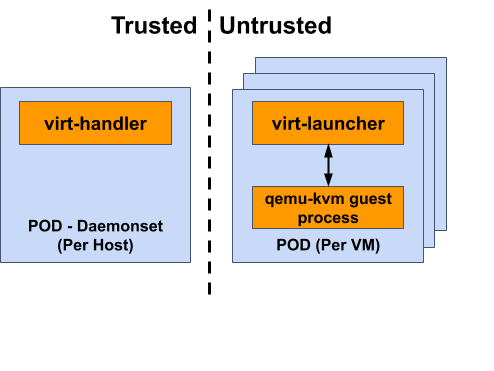

For KubeVirt, the separation between trusted and untrusted components comes when users can execute their own third party logic within a component’s environment. We can clearly illustrate this concept using the boundary between our two host level components, virt-launcher and virt-handler.

Establishing Boundaries

The virt-launcher pod is an untrusted environment. The third party code executed within this environment is the user’s kvm virtual machine. KubeVirt has no control over what is executing within this virtual machine guest, so if there is a security vulnerability that allows breaking out of the kvm hypervisor, we want to make sure the environment that’s broken into is as limited as possible. This is why the virt-launcher’s pod has such restricted cluster and host access.

The virt-handler pod, on the other hand, is a trusted environment that does not involve executing any third party code. During the virtual machine startup flow, there are privileged tasks that need to take place on the host in order to prepare the virtual machine for starting. This ranges from performing the Device Plugin logic that injects a host device into a pod’s environment, to setting up network bridges and interfaces within a pod’s environment. To accomplish this, we use the trusted virt-handler component to reach into the untrusted virt-launcher environment to perform privileged tasks.

The boundary established here is that we trust virt-handler with the ability to influence and provide information about all virtual machines running on a host, and limit virt-launcher to only influence and provide information about itself.

Securing Boundaries

Any communication channel that gives an untrusted environment the ability to present information to a trusted environment must be heavily scrutinized to prevent the possibility of privilege escalation. For example, the boundary between virt-handler and virt-launcher is meant to work like a one way mirror. The trusted virt-handler component can reach directly into the untrusted virt-launcher environments, but each virt-launcher can’t reach outside of its own isolated environment. Host namespace isolation provides a reasonable guarantee that virt-launcher can’t reach outside of its own environment directly, however we still have to be mindful about indirection communication.

Virt-handler observes information presented to it by each virt-launcher pod. If a virt-launcher environment is able to present fake information about another virtual machine, then the untrusted virt-launcher environment could indirectly influence the execution of another workload.

To counter this, when designing communication channels between trusted and untrusted components, we have to be careful to only allow communication from untrusted sources to influence itself and furthermore only influence itself in a way that can’t result in escalated privileges.

Mutual TLS Authentication

There is a built in trust that components have for interacting with one another. For example, virt-api is allowed to establish virtual machine Console/VNC streams with virt-handler, and live migration is performed by streaming information between two virt-handler instances.

However for these types of interactions to work, we have to have a strong guarantee that the endpoints we’re talking to are in fact who they present themselves to be. Otherwise we could live migrate a virtual machine to an untrusted location, or provide VNC access to a virtual machine to an unauthorized endpoint.

In KubeVirt we solve this issue of inter-component communication trust in the same way Kubernetes solves it. Each component receives a unique TLS certificate signed by a cluster Certificate Authority which is used to guarantee the component is who they say they are. The certificate and CA information is injected into each component using a secret passed in as a Pod volume. Whenever a component acts as a client establishing a new connection with another component, it uses its unique certificate to prove its identify. Likewise, the server accepting the clients connection also presents its certificate to the client. This mutual peer certificate authentication allows both the client and server to establish trust.

So, when virt-api attempts to establish a VNC console stream with a virt-handler component, virt-handler is configured to only allow that stream to be opened by an endpoint providing a valid virt-api certificate, and virt-api will only talk to a server that presents the expected virt-handler certificate.

CA and Certificate Rotation

In KubeVirt both our CA and certificates are rotated on a user defined recurring interval. In the event that either the CA key or a certificate is compromised, this information will eventually be rendered stale and unusable regardless if the compromise is known or not. If the compromise is known, a forced CA and certificate rotation can be invoked by the cluster admin simply by deleting the corresponding secrets in the KubeVirt install namespace.